“Radical Trust” and Teacher Agency Drive Deeper Change in Farmington

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the first post in a series about the Farmington Area Public Schools in Minnesota. Links to the other posts are provided at the end of this article.

Jay Haugen is Minnesota’s 2019 Superintendent of the Year, and his leadership has helped the Farmington Area Public Schools make great strides in advancing competency-based education. After 30 years in administration, Haugen has adopted a philosophy of “radical trust” in his staff, based on his experience that top-down initiatives fail to bring deep and lasting change.

During visits to Farmington High School and Boeckman Middle School, about 20 miles south of Minneapolis, I spoke with Haugen and Jason Berg, Farmington’s Executive Director of Educational Services. This post focuses on their philosophy and experiences with moving toward more personalized learning. Other posts in the series will explore specific changes in curriculum, instruction, assessment, and scheduling.

Promoting Agency, Not Compliance

Jay Haugen: I’ve tried to make big change my whole career, but for decades I’ve watched all the right stuff come to nothing. So we don’t talk about “rolling out” changes anymore. That hasn’t been our language for the past seven years. We don’t “run initiatives.” The central office doesn’t decide what people should do and then schedule staff development for everyone on those topics. It’s very organic. We invite people to innovate, we get them inspired about our direction, and we unleash our staff and provide the supports they need. This has led to many types of competency-based innovations in our different schools, disciplines, and grade levels.

One of our top words is “agency,” and that’s for both students and staff. We do not tell staff what to do and how to do it. I think that’s what been wrong forever. Everything emanates from our strategic plan, and our purpose—to ‘ensure that every student reaches their highest aspirations while embracing responsibility to community.’ As long as staff are connecting to our purpose, we’re going to honor their agency and their ability to bring about that result.

We need to go slow to go fast. District offices tend to wish that people would all just get on board with mandates, but what you get is compliance. Then five years later you wonder what happened to your initiative. So the issue is how you go about it. You need to realize that you can’t tell a human what to do and how to do it. You just can’t! We won’t accept it! We will pretend. We will comply. Compliance is the 10% solution, because it makes your big initiatives become tiny increments that don’t keep pace at all with our world. So we need to do something different. The leap is radical trust—preserve people’s agency, and let them self-organize.

I like to think that we’re going to get to a tipping point where competency-based will just become the way things are done, but in the meantime I think we’re on the right path. What’s happening now in Farmington seems just like in natural systems, where change is slow, slow, slow, and then suddenly takes off. The acceleration is unbelievable. But it took seven years for us moving in this strategic direction to get there. And now we’ve given hundreds of tours in the past two years with people who want to know more about what we’re doing.

The Traditional System is Not Broken

JH: We also need to acknowledge that the traditional system is not broken. It was meant to be inequitable. It was never made to do the things that we’re asking of it now, and it will defy us trying to change it. We can’t make our current system much better. It was meant to sort and select, pick winners and losers. It takes a small array of the skills and talents in the world and says, “Well, if you can do those things, you’re going to have a pretty good time in school. But if your passions lie outside that, then you need to check your passions at the door for a long time.”

The fact that kids who have something inside them that’s of great value to the world, that they can build a life on, but they can’t get credit for it in school, to me is just crazy-making. And so what we’re trying to do is say, “You have a passion and something you really want to spend time on? You should get to do it in school. And you should be the one driving it and making it your own learning pathway.”

Now there are things that everyone needs to learn, but it’s not that much. The traditional system has turned that on its head and said that 85% of what everyone needs to know is the same. We’re trying to figure out a way to transition to a whole new system.

Asserting Local Control

JH: I sometimes receive calls from the department of education after they read in the paper that our board is asserting their local control and just passed a resolution that conflicts with a requirement from the state. The current system doesn’t support our strategic plan, so we needed to make changes. We did a lot of work with our board to explain the strategic plan, and how the current system would need to be reorganized to meet its goals. The board understands what we’re going after.

One example of an alternative structure we created is flex days, where students don’t come into school and can work from anywhere using our full digital platform. We had seven or eight this year due to weather, and others we schedule in advance because it’s a fabulous way for students to learn. This is something we have been doing for years and it’s now happening in many districts in Minnesota, and there is some legislation supporting it. The state opposed it initially because it wasn’t counted as instructional time, but we have analytics to demonstrate how students are interacting meaningfully with our digital platform on those days. Now when you have bad weather days, the learning doesn’t have to stop.

The school board has way more authority than people think they do. They actually have some pretty broad authority. And the way statutes are generally written, the stuff we’re doing I think is all allowable. In our experience, some of the state department of education rules are more restrictive than the actual statutes.

And then people say “But what are we going to measure? Don’t we need to measure it?” The problem is that when you compare standardized tests to success in life or success in college, there’s very little relationship, and that’s because you’re not measuring what’s important. What’s important are these other things”—gesturing to a slide that said:

All 18 year olds should be able to:

- Talk to adults and advocate for themselves

- Manage workflow

- Handle interpersonal problems and cope with ups/downs

- Accept challenges and handle failing through perseverance/grit

Jason Berg: One way we demonstrate to our board that our kids are learning is we bring them to talk to the board all the time—a wide range of students, kids who usually wouldn’t get the opportunity, such as kids who are credit-deficient, and it’s unfiltered. One of these groups of students recently said they wanted to go talk to the board, and they spoke for 35 minutes. They could really talk about their learning. It was awesome.

JH: They could talk about their future, and they knew they could carry a project, knew they could talk to adults, things they had never gotten in school before, and that’s what we told the board our students are learning.

That’s what we want. We don’t care about the rest of the stuff. We didn’t tout when our state test scores were good, and we don’t apologize when they’re bad. We let people know that test scores are not what we’re after. We really, really do. Many of our families opt out of the tests, because they know they’re not good for their students’ learning. We have a scorecard of what we’re looking for in our district, and only one-sixth of it has anything to do with standardized tests, and we only include that part because we have to.

District Scorecard

District Scorecard

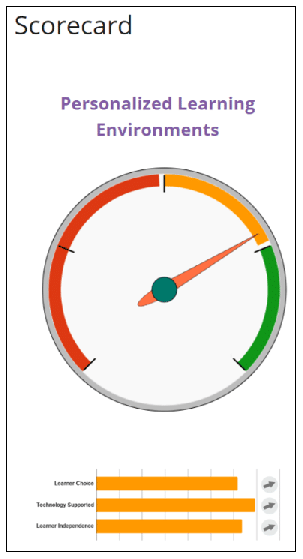

Farmington’s district scorecard warrants a closer look. It provides useful ways of thinking about, assessing, and making progress toward key goals. For example, under Personalized Learning Environments, they assess Learner Choice, Technology Support, and Growing Learner Independence. They include the surveys they used to assess these dimensions, and then they provide compelling, color-coded graphics to demonstrate their rating in each area. They use similar methods to rate their Culture for Learning and Innovation, Impact of Learning and Service, and other dimensions. These types of measures can provide one of many types of useful alternatives to traditional assessments.

Other Posts in the Series:

- Shifting the English Department to Competency-Based Learning

- Shifting the English Department to Competency-Based Assessment

- Interstellar Time at Boeckman Middle School

- Innovative Scheduling: Digital e-Learning Days and Academic Support Periods

Learn More:

- Empowering Teachers as School Leaders at Four Rivers

- CBE Quality Principle #5: Cultivate Empowering and Distributed Leadership

- ACTIONS – Ideas and Strategies for District Leaders

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.