Shifting the English Department to Competency-Based Learning

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the second post in a series about the Farmington Area Public Schools in Minnesota. Links to other posts are provided at the end of this article.

The administration of the Farmington Area Public Schools believes that their strategic plan, combined with “radical trust” in teacher agency, has led personalized learning to flourish in ways that are deep and expanding. Rather than prescribing what exact shifts should happen, they believe that changes in practice will emerge more naturally over time and with greater buy-in by giving teachers time and resources to support new ways of thinking and practicing.

The administration of the Farmington Area Public Schools believes that their strategic plan, combined with “radical trust” in teacher agency, has led personalized learning to flourish in ways that are deep and expanding. Rather than prescribing what exact shifts should happen, they believe that changes in practice will emerge more naturally over time and with greater buy-in by giving teachers time and resources to support new ways of thinking and practicing.

Four English teachers at Farmington High School—Ashley Anderson, Adam Fischer, Sarah Stout, and John Williams—explained that these changes have played out in their department as a gradual process of becoming more focused on what each student wants. Over time, their work has become more closely oriented with all five parts of the working definition of competency-based education.

Wherefore Art Thou, Student Engagement?

Three years ago at a PLC meeting, the teachers and an administrator decided to expand the curriculum, which included readings such Romeo and Juliet and To Kill A Mockingbird, to include a wider range of traditional and contemporary books and authors. They believed this would increase student engagement and the curriculum’s cultural responsiveness. The PLC thought carefully about what outcomes they wanted and realized that the skills and dispositions students needed could be developed from this wider range of readings. Not everyone needed to read the same books at the same time with the teacher leading from the front of the room.

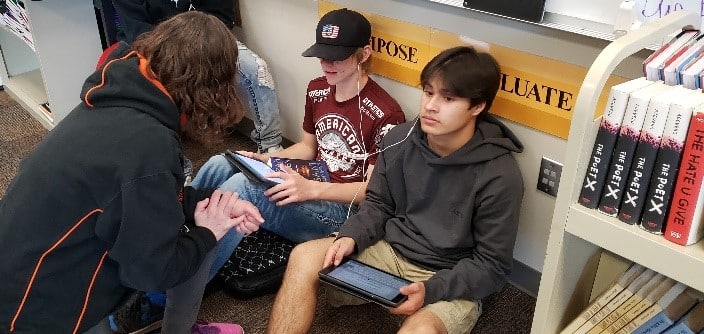

So they bought sets of 13 new books. The students not only began choosing what books they wanted to read, they also began leading their own book groups. The teachers helped them build higher-level skills such as leading a discussion and developing engaging questions. “So we get all of that ‘standards stuff’ in there,” one teacher explained, “but then it’s about them taking charge and leading the conversation.”

Some of the new titles were The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo, Flight by Sherman Alexie, Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson, and All American Boys by Jason Reynolds—acclaimed books with diverse authors. The teachers described students coming in and saying things like, “Wow—do you know what’s in this book?!” and that it was the first book they had ever read cover to cover, sometimes in one weekend.

Focusing on Student Interests

The English department believes that students should be spending more time meeting ELA standards through their interests, which has led to “passion projects” as a major component of the year. (These projects didn’t fit well with traditional grading, which was part of the impetus for shifting to competency-based grading.) Each student researches something different, and the teachers report that the students invest more in their learning because they’re more interested.

Students’ passion projects have included developing a business plan for a football camp, researching the genealogy of a horse, and researching acrylic painting techniques. All projects involve interviewing experts, doing non-fiction writing, and a hands-on component such as building a bike shed on campus or making time-lapse video of a painting in progress. Then students present their final projects at an exhibition night. (Yes, the horse came to school for the genealogy presentation.)

All of this personalization requires teachers to use their time in very different ways. The teachers agreed that shifting from sage on the stage to guide on the side freed up time for other activities. “We may start with a mini-lesson, but then give students lots of time to be working, doing research, meeting with each other, and I’ll be conferencing with them. Some students leave class and go to the writing center and get feedback. Some go to the media center because they want to be typing on a keyboard. Students do most of their reading and writing during class time while I’m meeting with other students.”

The teachers are also shifting how they incorporate and assess required content, as described in the next blog post about Farmington. The teachers and administration have been pleased with the results. Superintendent Jay Haugen said, it’s stunning when you go into these teachers’ classrooms and talk to the kids. I’m a 30-year administrator, and in the past when I’ve gone in to talk to kids, they’re looking at their feet and it’s like they’re trying to remember what the teacher told them so they can tell me; that would be the conversation! But here kids are doing stuff that they love and they understand and they’re the expert in! And so they’re talking to you like a full adult. They’re looking at you in the face. They’re excited about what they’re talking about. And they’re confident now that they have something inside them that’s worth something to the world. Like at the showcase for the passion projects, the students aren’t just turning something in to a teacher. They have to defend it in public, and that’s happening all across the district now. We constantly have showcases and shark tanks and kids get to do real stuff.”

The experience of Farmington High School’s English teachers demonstrates that competency-based shifts can happen incrementally as teachers’ thinking changes and they perceive the need to develop new strategies. As described in subsequent posts, other shifts are happening throughout the district, such as greater use of self-paced work, innovative scheduling, and helping students develop agency.

Other Posts in the Series:

- “Radical Trust” and Teacher Agency Drive Deeper Change in Farmington

- Shifting the English Department to Competency-Based Assessment

- Interstellar Time at Boeckman Middle School

- Innovative Scheduling: Digital e-Learning Days and Academic Support Periods

Learn More:

- Developing a Competency-Based ELA Classroom

- CBE Quality Principle #7: Activate Student Agency and Ownership

- 10 Tips for Developing Student Agency

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.