Competency-Based Education in Rural Schools

CompetencyWorks Blog

CompetencyWorks has featured visits to rural schools, enabling us to examine how competency-based education has taken hold in rural districts. After reviewing past blog posts and reports, and obtaining updates from the websites of the schools or their state departments of education, we are highlighting the following districts:

Chugach, Alaska (blog series and report)

Chugach, Alaska (blog series and report)- Eminence, Kentucky (blog post)

- Deer Isle-Stonington, Maine (blog series)

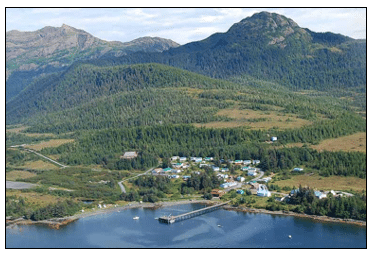

Chugach School District, Alaska

School districts don’t get much more rural than Chugach. The central office is in Anchorage, but the schools are in small towns and villages across 20,000 square miles of Prince William Sound. The Whittier Community School, for example, served 33 students in the 2017–18 school year. The district also served 377 homeschoolers across the state with teachers who serve 40 to 60 students at a time.

Chugach was the first K–12 district in the United States to move from a time-based system to a performance-based system in which graduation was based on meeting performance targets rather than earning credits. Their first steps were in 1994, in response to concerns about low student achievement levels. This led to a district transformation that resulted in a performance-based learning and assessment system and dramatic improvements in student outcomes.

In 2001, Chugach was the first public school district to receive the prestigious Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award , a presidential-level honor that recognizes exemplary U.S. organizations that demonstrate “an unceasing drive for radical innovation, thoughtful leadership, and administrative improvement.” The award was for the school district’s continuous improvement, whole-child approach, rich and transparent data, and advances in educational achievement. In fact, from the 1992–93 school year to the 2013–14 school year, the percentage of students scoring at grade level on state assessments rose from less than 25% to 80% in reading and from less than 25% to 58% in mathematics.

Education in Chugach utilizes many of the quality principles of competency-based education. For example, the competencies are transparent and the learning management system enables students and parents to know where they stand in terms of performance in close to real time. Students have multiple ways to demonstrate competency and moving to the next level in a given content area requires evidence based on student reflection, skills assessment, and performance assessment. In addition to the CompetencyWorks resources cited above, the book Delivering on the Promise: The Education Revolution provides in-depth information about the approach to education in Chugach. It’s a great read and comes recommended from the team at CompetencyWorks.

Eminence Independent School District, Kentucky

Eminence Independent School District, Kentucky

Eminence Elementary School and High School together serve almost 900 students in a rural district 40 miles east of Louisville. When Eminence began its transition to a competency-based system, it did something that was very difficult but would be nearly impossible in a larger district—they interviewed every student in the district, in focus groups of 15 students each, asking them to share what they didn’t like about school and what they wanted it to be.

Based on what they heard, the district enlisted students in being part of the solutions, and that led to greater development of student agency than in traditional districts. Students are members of site-based decision making with full voting privileges, teachers work to develop interest-based courses centered on student interests (as well as their own), and students have opportunities to design and even lead courses. Student-led conferences begin in third grade.

The district’s 1:1 program has more than one device per student, enabling them to make substantial use of adaptive software such as Dreambox, Lexia, and Reading Plus to support blended learning and differentiation. This has enabled many students who entered with low skill levels to make rapid progress. During our 2015 visit, Eminence was in the process of developing a competency-based system that included organizing teachers to meet students at their level, not based on age-based cohorts; setting graduation expectations based on skills, not just time-based credits; creating a grading system based on achieving mastery of competencies rather than averaging; and promoting advancement based on demonstrations of mastery at selected grade levels. For a deeper dive into Eminence, watch Superintendent Buddy Berry’s keynote address (starting at 40:58) at the 2015 iNACOL Symposium.

Deer Isle-Stonington School District, Maine

Deer Isle-Stonington School District, Maine

The towns of Deer Isle and Stonington, about three hours north of Portland, are one large island plus many small islands nearby, with a combined population just below 3,000 residents. The town turned to competency-based education in 2008 when a new high school principal arrived, after a decade when several principals had come and gone. The high school had 172 students and there had been 300 suspensions in the past year, and the graduation rate was 57%, the lowest in the state. As the development of CBE progressed, the school’s graduation rate rose to 90% for three years.

The principal said that competency-based education, or “proficiency-based learning” as it is called in Maine, enabled the school to offer “cool pathways to inspire and engage kids” and be creative in how they structured learning. When students were missing credits, using proficiency-based learning also permitted flexibility to organize learning so that students could earn more credits within the same amount of time. The school had an intervention block for students to get extra help, as well as literacy specialists who would go into classrooms and work closely with students who were struggling.

The reforms in the district included developing professional learning communities of teachers that collaborated to build consistent academic expectations across the school. This involved creating cross-department PLCs, because in such a small school many departments consisted of a single teacher. The school also participated in external coaching—with the Great Schools Partnerships to support development of PLCs and the leadership team, and with the Rural Aspirations Project to develop competency-based learning and two optional specialized learning pathways (arts and marine studies). The marine studies pathway helped the community legitimize the knowledge of fishermen—through authentic student projects, field work, and guest experts from the local fishing industry—countering the perception that “if you weren’t smart enough to do something else, you went fishing.”

Conclusions

Some rural districts have engaged in major shifts toward competency-based education, and more districts nationwide continue to do so—stay tuned for dispatches from other states later this year. The stories of Chugach, Eminence, and Deer Isle-Stonington show that competency-based education can be associated with improvements in academic achievement and attainment. They also suggest that small size can be an asset, because it can facilitate dialogue within the school and the broader community around the vision for change and the long-term, collaborative work of deep reform.

See also:

- Driven by Student Empowerment: Chugach School District

- Chugach School District: A Personalized, Performance-Based System

- A Conversation with Buddy Berry in Eminence Kentucky

- Deer Isle-Stonington High School: Turning Around the Culture

Note on selecting districts for this post: The U.S. Census Bureau defines “rural” as being outside of an urban area. Fortunately, they take it a step further: their smallest urban area designation is an “urban cluster,” which contains between 2,500 and 50,000 people. Purists may note that the 2017 population of Eminence, Kentucky was 2,569, just above the census limit, but I won’t split hairs—the issues relevant to competency-based education still hold.

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.