The Power of Choice: Increasing Novel Reading From 21 Percent to 87 Percent

CompetencyWorks Blog

For those of us who have always taught with an end-goal in mind, competency-based education isn’t that big of a shift. We’ve always thought about assessment and the way we’d bring our students to success. In my opinion, the biggest difference between competency-based education and traditional education is that our focus is less on content and recall, and more on differentiation and application.

As an eleventh-grade English teacher at Sanborn Regional High School in New Hampshire, I have three major competencies: reading, writing, and communications. My students don’t earn one grade for the course; they have to pass all of their competencies in order to pass the course.

Traditionally, students in English classes have always practiced these skills. English teachers have always used literature as a vehicle of instruction, have instructed writing, and have encouraged discussion.

Traditionally, students in English classes have also habitually fake-read novels, plagiarized writing, and sat silently during class discussions. (I know that I did.)

In my competency-based classroom, that kind of fake-reading just doesn’t happen anymore. How do we get there? It’s all about student choice.

In our class, we read constantly.

Choice reading is the backbone of our curriculum. Modeled after Penny Kittle’s classroom, for the first ten minutes of class, we read to read. We read to enjoy reading. No matter what, we read for those first ten minutes.

While students read, I conference, I model my own reading, I encourage abandonment of books, and I high-five over completed choice novels.

While students read, I conference, I model my own reading, I encourage abandonment of books, and I high-five over completed choice novels.

But I don’t formally assess them on their choice novels. When my students finish their choice books, they put a link on a paper chain, give me a high five, and pick another book. The chain wraps around our classroom, and at the end of the year, we take a photo. That’s it. It’s great.

We read the things we like to get better at reading the things we don’t like. In our classroom, we do work with “the classics.” I explain to them that we might not always love the books that we’re assigned to read in an English class, but we will learn from these novels. I tell them that reading the classics is hard, and that’s why we also read the things we like while we’re reading our assigned novels.

I don’t teach whole class novels anymore.

Instead, I offer students four classic novels that fit under the same theme. During class, I meet with groups/pairs/individuals and we talk through the novel. While I’m meeting with groups, the rest of the class reads their assigned novel, pulling discussion points as they read.

Some students listen to the novel on audio, some read silently, and some read while listening the audio.

Are they still “reading” when they listen to the audiobook?

Are they still “reading” when they listen to the audiobook?

Not traditionally, but they may be “reading” more than they would be if they didn’t have access to the audiobook, right?

In competency-based education, the way that students access the text doesn’t make a difference to the end result. My students are assessed on their evidence-based analysis and interpretation of these texts.

The way they accessed the text doesn’t matter, especially because they are also reading their choice novels for the first ten minutes of class, alongside their assigned text.

Here’s the proof that giving students choice around reading builds competency in reading.

I had this same group of students as freshmen. We read To Kill a Mockingbird as a whole-class novel. I thought it was great! They came to class prepared with notes on the chapter I’d assigned for homework. Students participated in whole-class discussions, and they did well on their assessment.

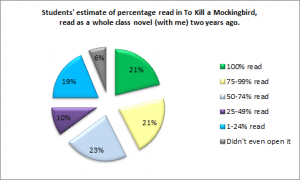

When asked anonymously how much of that book they actually read, they admitted that they’d used SparkNotes for most of the book and reported the following stats:

What a bummer. When asked why, their answered varied from, “It was boring,” to “I just didn’t have time to read it at home.” I get it.

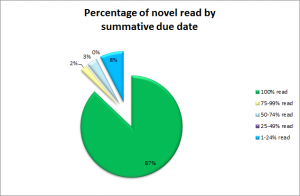

I tracked their pages as they read their self-selected classics, too.

On a regular basis, I checked in with students about their page numbers. They didn’t lie, because I told them I was gathering data on how well this was working. I didn’t get mad if they were behind. So they were honest.

When polling my students on their summative due date, 87 percent of them had read the entire novel.

How do I know that they really read it? I watched them read it.

Why did they read it? Students reported that having time to read the novels during class was the number one thing that motivated them to keep reading. Following closely behind was having the choice of novels.

Many teachers claim students are successful in English class when they can correctly answer comprehension questions or when they can write a literary analysis essay.

I argue that they’re only successful in English class when they’re actually reading, writing, and speaking.

We’ve read 260 choice novels so far this year, and 80 assigned novels.

Somewhere else, an entire classroom of students may not have even opened a book.

I like this way better.

See also:

- Learner-Centered Tip of the Week: Simple Moves to Increase Engagement

- Engagement Templates: 6 Ways to Structure Learning Experiences

- How My Understanding of Competency-Based Education Has Changed Over the Years

Crystal Bonin is an English teacher as Sanborn Regional High School in Kingston, New Hampshire. She is strong advocate for student choice in reading and writing, and regularly reads and writes obsessively inside and outside of her classroom. In her seven years at Sanborn, she taught for six years within the award-winning Freshman Learning Community, developing competency-based curriculum and assessment. This year, she has been working to overhaul her Junior Lit classroom into a full-press readers/writers workshop. She lives in Kittery, Maine with her husband and cats. Follow her on Twitter at @_readreadwrite or on her blog at www.readreadwrite.wordpress.com.