Supporting Educators as Ambassadors for Mastery-Based Learning

CompetencyWorks Blog

“Teachers tell us ‘we know so much more about supporting students, it would feel like malpractice to go back to how we used to teach,’ and parents will tell you the same thing: ‘we never want our students to go back to the other way, because this way leads to independence and real learning.’”

These words from Ellen Hume-Howard, former curriculum director for Sanborn Regional School District (NH), paint a picture of a school community in which parents and teachers speak a common language and pursue common goals for student learning. However, as Ellen is quick to add, this partnership is the result of years of effort. Educators and parents came to value innovations like mastery-based learning because they took the time to forge relationships, build trust, and co-create new definitions of student success.

Ellen is one of many educators in the Next Generation Learning Challenges (NGLC) community who has experience in communicating with stakeholders about mastery-based learning. We spoke to three school leaders and the authors behind Communications Planning for Innovation in Education to learn about their communications strategies and particularly the role of teachers in this work. They tell us that communicating effectively about innovations, and especially the “why” behind them, is essential. Classroom educators are the most visible—and powerful—ambassadors for next gen learning models to the broader school community.

To explore the key role teachers play as communicators, we tapped into the knowledge and experience of NGLC school leaders and other innovators to help us answer these questions:

- Why are classroom educators so important to the work of communicating about innovative teaching and learning?

- What kinds of support should schools provide to educators to do it well?

Classroom Educators Tell the Story of “Why?”

With another school year about to begin, educators are working full tilt to get ready. Principals are preparing professional learning activities and reviewing student data, while teachers are counting supplies, planning lessons, and setting up their classrooms. The “back to school” season is a tradition, a familiar part of the rhythm of teaching and learning familiar to parents from when they were in school.

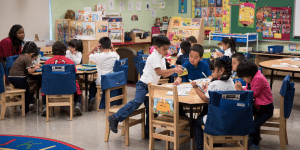

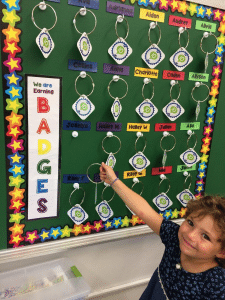

However, the more schools engage with mastery-based learning and other student-centered, personalized innovations, the less learning looks like it did when parents were students. In place of rows of students at desks, we see groups collaborating around a table on a student-designed project. Instead of “all eyes on the teacher” as the sole repository of knowledge, we see learners setting goals and making choices as they navigate personalized pathways. Traditional letter grades give way to mastery-based measures, like the competency badges used in Elizabeth Forward School District (PA) or Sanborn schools’ “running report card.” Even time-honored concepts like “grade level” become less distinct.

Like other innovative schools, CICS West Belden has committed to a personalized learning model with new goals for student learning. “Those days are long gone when just doing the work put in front of you was enough, either in school or as an adult,” Colleen explains. “Now it’s about helping students know who they are. Once a child can articulate what kind of a learner they are, what makes them curious, there’s such a different investment in learning. Kids take the wheel.”

Colleen Collins, director of Chicago International Charter School (CICS) West Belden, a K–8 charter school, puts it this way: “You’ve seen the pictures of classrooms from the 1920s, the 1950s, and even today. For a long time it was a lot of teacher heavy lifting, and students were not doing the work of learning. They were well behaved and could say what they were doing, but not what they were learning. It was about compliance.”

Colleen Collins, director of Chicago International Charter School (CICS) West Belden, a K–8 charter school, puts it this way: “You’ve seen the pictures of classrooms from the 1920s, the 1950s, and even today. For a long time it was a lot of teacher heavy lifting, and students were not doing the work of learning. They were well behaved and could say what they were doing, but not what they were learning. It was about compliance.”

Mastery learning looks different because it is different. Caitlyn Herman, head of schools for Summit Public Schools in the Bay Area, calls to mind the challenges these changes pose for communicating with stakeholders: “People will think about their own experiences in school, so everyone who walks through the door needs to be reminded of the ‘why’ of what you are doing and what the parent wanted from the school. It’s about students having the skills, habits, and dispositions to pursue their passion.”

As the primary points of contact for students and families, classroom educators represent your school model every day. Kira Keane, a partner at The Learning Accelerator, believes that “teachers are one of the most trusted messengers for parents and the community about what is happening in the classroom.” They are also the ones who will hear the “why?” questions.

Glossy brochures and interactive websites can be useful for communicating to the wider community, but the consensus among the leaders we talked to was clear: investing time to support teachers pays off—and not just for improving communication. Conversations about a school’s vision, goals for student learning, and a shared theory of action not only help educators better articulate about innovative practices, but this communal sense-making also improves the practices themselves.

Time to Think, Together

School leaders tell us that effective communication begins with providing educators with a common vision and messages aligned with that vision. Janice Vargo, associate partner at Education Elements, expresses it this way: “There’s nothing more frustrating to teachers than when it’s unclear why their district is moving in a certain direction, how this change relates to other initiatives or focus areas, and why the district or school thinks this is best for students.”

If schools want to equip educators to answer the “why” questions about the learning environment, pedagogy, assessments, and reports on student progress, school leaders need to build capacity in teachers to understand, own, and communicate about what they are doing.

Capacity-building takes time, but if you are serious about developing an effective communications strategy, this is not a corner to cut. “Allow teachers the time and space to find their voices; storytelling is one of the most effective ways to quickly and effectively communicate important messages AND emotions,” adds Kira, highlighting the role of feelings in how people experience change and innovation.

“You can never over articulate the mission,” Colleen tells us. And when it comes to supporting teachers to communicate about your next generation learning model, “practice and ownership are needed-—have you ever tried to give someone else’s presentation?”

Our experts also suggest giving teachers time to find their voices and platforms to tell their stories. For example, educators can practice communicating about their teaching and the thinking behind it to a wider audience via social media, podcasts, blogs, and guest columns.

Ways to Build Educators’ Communication Competence

Though all of the experts I talked with agree that dedicating time to help educators “own” the mission is vital, each school or district finds its own ways of using that time and building that capacity. Here are a few examples of how it might look:

- Sanborn Regional Schools invest in creating strong teacher leadership structures where educators can grapple with the “why” questions. Educators collaborate daily in professional learning communities (PLCs), and the traditional department head has been replaced by a PLC lead. Using this configuration, peers engage with research and build expertise in practices associated with their student-centered model, such as learning progressions, performance assessment, and developing student agency. They also create rubrics, with parent input, designed to be meaningful to a student and parent audience. “This expertise has given our teachers confidence,” Ellen explains. “We have focused on using research as the basis for decisions, and teachers rely on research to communicate” with families.

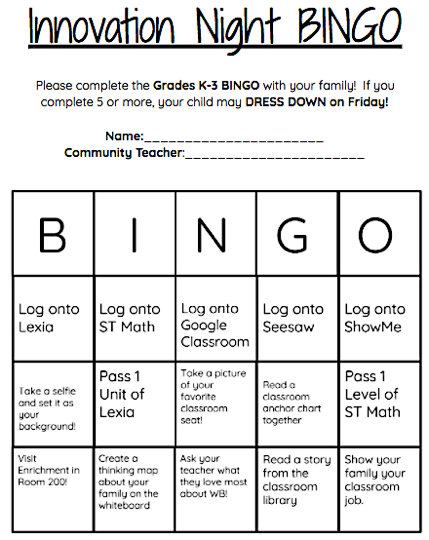

- At CICS West Belden, educators collaborate to organize events in which parents and students learn about—and even live—the mission. For example, teachers design Innovation Nights for families to explore key features of the school’s model. Parents also get the opportunity to experience learning as the students do, as with this Tech Innovation Scavenger Hunt “Bingo” game:

- Another way CICS West Belden’s educators help families live the model is via flipped conferences, in which students and parents drive the conversations about data, learner profiles, and emotional growth. Teachers are trained not only to explain and answer questions about the mission but also how to act as listeners and facilitators, modeling the student-centered practices and student agency of the classroom. In other words, there’s more showing than telling about practice in this communication strategy.

- Summit Public Schools leverage multiple one-on-one touch-points with parents throughout the year, and Caitlyn shares that “every one starts with a refresh and an explanation of how what we are doing right now connects to the mission.” Considerable professional learning time is spent to “deeply embed a knowledge of the mission to make educators the ambassadors.” In Summit’s model, teachers serve as mentors for a select group of students. They receive in-depth training and support for this role, which includes frequent contact with parents, as well as 45-minute family meetings twice a year. Talking points, role-playing, and even school leader “ride-alongs” prepare each educator to serve as a mouthpiece for the Summit model. For each touch-point, “part of the task is always connecting to goals for student success…every moment of interaction is a reframing of that.”

Communications Resources for Educators

As these examples illustrate, deep understanding of how personalized, learner-centered practices align with your mission and definition of student success cannot be accomplished with a “one and done” professional learning event. However, once educators have done the foundational thinking to own the mission and model, school leaders can provide time and resources to support them in communicating the “what” and the “why” of next generation learning.

For parent events like Back-to-School Night at CICS West Belden, school leaders create a “shell” slide deck about the school’s mission and goals. Educator teams then work with an instructional coach to customize the presentation for their grade levels and teaching team. This process results in what Colleen calls “a collaboratively created slide deck for common language and consistency, but each teacher delivers it as his or her own.”

Other school leaders provide educators with resources like this Curriculum FAQ and messaging document from Sanborn, which define and give the “why” behind competency grading. CICS West Belden’s Teacher Talking Points: Standards-Based Grading explains, in English and in Spanish, what competency-based grading is and how it can inform educators’ conversations with parents about student progress.

Materials that were originally conceived as public-facing documents can also be useful to provide language to educators. This resource from Charleston County Public Schools (SC) ties personalized learning to goals for student learning like problem-solving and contributing to the common good. This FAQ invites community members of the Fairbanks (AK) North Star Borough School District to ask questions about personalized learning to build an online bank of shared community knowledge.

Last of all, do not overlook the power of peers. Members of the NGLC community are eager to share what they’ve learned about working together to craft and communicate answers to the “what” and “why” of their innovations.

For more on communicating about personalized, mastery-based learning, see the resources below:

- Communications Planning for Innovation in Education is a joint publication by The Learning Accelerator and Education Elements, including our experts Janice and Kira quoted above. It is a step-by-step guide for school leaders with profiles of districts and exemplar tools from various points throughout the process.

- “Communication and Outreach Strategies for Leaders Shifting to Personalized Learning,” an archived webinar and slide deck from the International Association for K-12 Online Learning (INACOL), includes examples of communication strategies and outreach events from a variety of schools nationwide.

- “Student-led Conferences: Empowerment and Ownership” provides guidance on how to implement student-led conferences, including practical advice on scheduling and preparing students and educators.

- Cause Clarity offers bite-sized communications training videos that educators can access on demand.