Using Global Best Practices for School Self-Assessment and Action Planning at Monmouth Middle School

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the second post in a series about the Global Best Practices (GBP) tool from the Great Schools Partnership. It is an outstanding, free resource that offers a practical, step-by-step process for assessing schools to inform school improvement plans. It focuses on characteristics of high-performing schools and can help facilitate shifts toward high-quality competency-based practice.

This is the second post in a series about the Global Best Practices (GBP) tool from the Great Schools Partnership. It is an outstanding, free resource that offers a practical, step-by-step process for assessing schools to inform school improvement plans. It focuses on characteristics of high-performing schools and can help facilitate shifts toward high-quality competency-based practice.

The first post gives an overview of GBP. This article shares how GBP has been used by Monmouth Middle School in RSU2 in Monmouth, Maine. Their work advances several of the quality principles for competency-based education, such as developing processes for ongoing continuous improvement and organizational learning.

Developing a Self-Assessment and Action Plan

Principal Mel Barter explained that Monmouth, a school with grades 4–8, used Global Best Practices when they had a multi-year coaching and professional development contract with the Great Schools Partnership. She was a teacher on the school leadership team at the time, and they had a new principal who wanted to conduct GBP’s self-assessment and develop an action plan.

After recording their performance strategies and evidence for each GBP dimension, teachers scored the school on each dimension. The school’s leadership team used these scores to draft an action plan during the summer and presented it to the whole staff in the fall. Staff members volunteered to take leadership on the parts they were most interested in.

The Action Plan “got traction quickly. It made it so easy to talk about challenges and how we could make important changes,” Barter explained. “Having the Great Schools Partnership coaches was amazing. They did so much for us, and we still use their protocols.”

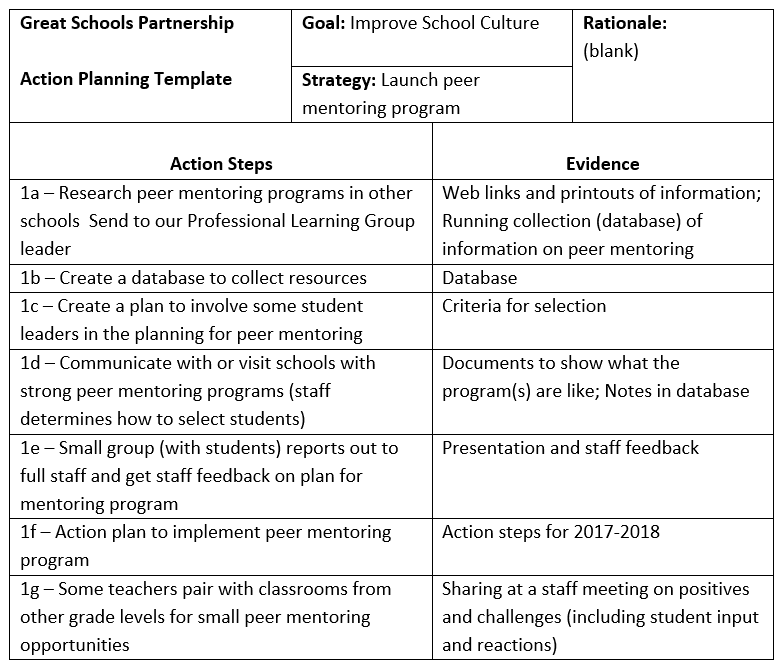

The full action plan for all GBP dimensions is available here. School culture was one priority area for the school’s action plan, and the school developed three strategies to improve school culture that they thought could help bring the school together:

- Launch peer mentoring program.

- Create school-wide activities for students (e.g., culminating events, celebrations, parent/career activities, 4–8 student council meetings).

- Restructure staff meetings and professional development opportunities.

Then they used the GBP Action Planning Template to lay out their action steps, evidence, timeline, leaders, other participants, and resources needed. The Action Planning Template below presents the action steps and evidence they developed for launching a peer mentoring program.

The complete Action Planning Template also includes these five columns:

- Timeline – Indicate when the proposed action steps will be carried and when they will be completed.

- Coordinator – Name the lead coordinator and supply any relevant information about the role.

- Participants – List the names of additional participants and describe their roles in the process.

- External Support – Indicate what role (if applicable) any external support provider will play in carrying out the action step.

- Resources – List the financial and material resources that will be needed to carry out the action step.

Implementing the Action Plan: Peer Mentoring

The teachers who were most interested in the peer mentoring strategy led its implementation. After doing research to understand how other schools do peer mentoring, they decided to start informally, with 8th-graders volunteering in 4th-grade classrooms in mentor-mentee pairs. “Like with everything, you just have to get started and dip your toe in the water,” Barter said. The 8th-graders helped the 4th-graders with school work, or they did a fun activity together.

The peer mentoring took place during academic assistance period, a school-wide scheduling structure that enabled flexible, multi-grade learning and support activities. The school maintained a Google Doc of what every student was doing during the academic assistance period, so they could check whether the mentor and mentee students were both free. (This type of scheduling and tracking innovation is very helpful for two key aspects of competency-based education – providing timely, differentiated support based on students’ individual learning needs, and enabling students to advance upon demonstrated mastery.)

The next year, more students wanted to participate. The school developed a seminar that trained students in peer mentoring. Barter said that both age groups love it. The older students feel helpful, important, and empowered. The younger students are thrilled to have the attention of an older student. The day before our call, Barter had seen a 7th-grade mentor just walking around the school talking with his 4th-grade mentee. She felt strongly that peer mentoring has been effective in improving school culture, and that several others strategies initiated as part of the GBP self-assessment and action planning process have also been successful.

Academic Growth through Authentic, Real-Life Experiences

The second action planning goal that emerged from GBP was “Support Academic Growth and Achievement,” and one of its strategies was “Incorporate Authentic, Real-life Experiences.” The school’s first step was starting a maker space in the building, called the Learning Lab. This enabled teachers to leave their classrooms and work with students on skills such as industrial arts and home economics that had become less available in the school curriculum.

It soon became apparent that the space was only being used by teachers who were comfortable leading these types of activities. In response, the school started broadening what they meant by “real-life learning,” so that all teachers would participate. That’s where the idea came from for the peer mentoring seminars described above. Other seminars have included podcasting the ongoing construction of Monmouth’s new school building, and developing a student group that uses the school’s 3D printers to address problems that arise in classrooms.

Barter reported that this strategy has been effective in supporting academic growth. Students are very motivated and tend to finish their seminar work at high levels. She has also seen a spillover effect, where seminars are increasing students’ engagement in other classes. In addition, the seminars have been a way to increase student agency, as they have proposed new seminars and participated in their planning and implementation.

The school district’s website provides helpful materials for parents/guardians that situate all of these activities within a proficiency-based learning framework. (“Proficiency-based” is another term for “competency-based,” and is the term mostly used in Maine.) The peer mentoring and academic growth strategies are both aligned with RSU2’s Five Tenets of Learning, which reflect key aspects of high-quality, competency-based learning:

- Classroom culture that encourages learner agency.

- Clear learning targets in a good progression.

- Gathering evidence to provide feedback about the learning target.

- Learners engaged in learning that is in their zone of proximal development and interest.

- Learning is applied and not simply tested.

Thank you to Principal Mel Barter for sharing Monmouth Middle School’s experiences with using the Global Best Practices self-assessment and action planning tool!

See also:

- Global Best Practices – A Practical Tool for School Self-Assessment and Action Planning

- Global Best Practices Self-Assessment Tool

- Global Best Practices Facilitators Guide

- Global Best Practices Research Summary

- Quality Principles for Competency-Based Education

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.