The Mastery Collaborative: Dozens of NYC Schools Support Each Other’s Reforms

CompetencyWorks Blog

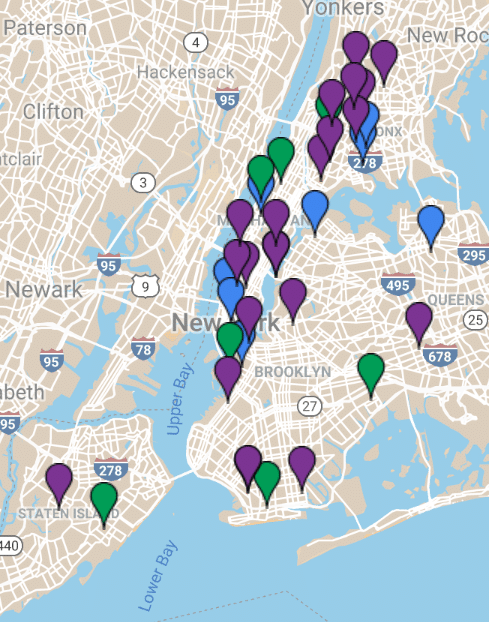

The Mastery Collaborative (MC) is a network of public middle and high schools in New York City that are shifting and working together toward greater implementation of mastery/competency-based and culturally responsive education practices. The network is led by the New York City Department of Education, currently with two full-time staff members and two part-time consultants, who support the work of dozens of member schools. Detailed background information about the Mastery Collaborative is available in past CompetencyWorks posts (see links below).

The Mastery Collaborative (MC) is a network of public middle and high schools in New York City that are shifting and working together toward greater implementation of mastery/competency-based and culturally responsive education practices. The network is led by the New York City Department of Education, currently with two full-time staff members and two part-time consultants, who support the work of dozens of member schools. Detailed background information about the Mastery Collaborative is available in past CompetencyWorks posts (see links below).

This is the first in a series of posts based on iNACOL’s recent visit to two MC member schools, participation in a roundtable discussion with faculty and students from several schools, and attendance at a professional development workshop on culturally responsive education.

Shifting to Mastery-Based and Culturally Responsive Education Takes Time

The Mastery Collaborative’s structure makes explicit an essential aspect of shifting to mastery-based and culturally responsive education (CRE)—that schools transform at different paces and to varying degrees. The 37 member schools span three tiers with different levels of implementation:

- Living Lab Schools have “effective schoolwide mastery systems with exemplary aspects to share with others.”

- Active Member Schools are “engaged in strengthening and spreading mastery/CRE practices, with a goal of ever-more-effective schoolwide implementation.”

- Incubator Schools are “in early stages of shifting to the MC’s mastery/CRE model.”

A fourth group, called the Friends of Mastery Collaborative (FOMC), contains hundreds of educators from 80 additional New York City schools, plus other states and countries, that are invited to participate inMC-hosted events, school visits, and professional development offerings. Some FOMC schools later become members, and all are exploring shifts toward greater mastery and CRE practices.

Noting this structure, and the progression it implies, can be useful for preventing “reform paralysis”—a possible name for the inability to get started because the shifts seem too daunting. Even the two Living Lab schools we visited, which have some of the more advanced mastery systems in the network, pointed out substantial areas where they still want to make progress. This is partly due to the time, thought, discussion, buy-in, and learning-by-doing needed to implement any deep innovation in schools, and partly due to institutional challenges such as traditional district-wide grading systems and high-stakes graduation exams. What’s clear is that there are many entry points and many ways to shift toward stronger implementation, and that’s what MC member schools are doing.

A Strong Professional Learning Community Helps Too

The collective wisdom and mutual support of the MC staff and the member schools are tremendous assets that provide inspiration, tools, and a motivating sense of accountability to a common vision. The MC staff host gatherings, facilitate conversations about practices and beliefs, and support sharing of resources across schools. They also facilitate site visits between member schools and for outside guests, and they arrange for mentor educators within the network to offer “office hours” to help members advance their mastery practices across subject areas and grade levels. Their professional development offerings include an Advancing Equity Series co-facilitated with the Center for Racial Justice in Education, as well as a four-day summer institute for New York City educators who want to improve their mastery-based and culturally responsive practices.

While having 37 member schools in a single city clearly provides great PLC opportunities, schools in other locations that want to develop their own PLCs around competency-based education can do it within a single school, district, or region. There is a group of five districts in one of the most sparsely populated states in the country who are meeting in May to strengthen their personalized and competency-based practices—I am scheduled to attend and report back.

We attended a roundtable discussion of faculty and students from about ten Mastery Collaborative schools where they provided much knowledge and inspiration to each other, including the following:

- In mastery education, the emphasis is on “learning” rather than “covering content,” where the teacher might focus on a set of 15 competencies over the course of the year and return to them repeatedly. This shifts the balance of learning more toward skills than content, although both remain important.

- Students in mastery-based schools come to think of learning as iterative, as a process rather than a moment in time. They have an expectation of revision and even failure. This is good, because later in life their professor, supervisor, or client will expect them to improve their own work—to assign themselves a revision. To facilitate this, some teachers ask students to mark up the needed revisions on their own papers rather than having the teacher go first.

- One teacher said, “We are working hard to slow things down so students can learn more deeply. That doesn’t always match the pace of learning expected by the district and state. So visitors might be impressed with the students’ thoughtfulness, but the district might say that your performance on conventional measures is inadequate.” Another teacher said that even 9th-graders in their first year in a mastery-based school do well on the state’s high school graduation exams. (That would be an interesting topic for systematic research.)

- An administrator from an international school, many of whose students are recent immigrants, said mastery education helps teachers differentiate education for students who arrive from very different backgrounds. For example, the school’s grading system not only separates academic performance from habits of work (such as cooperation or participation in class), but also considers English language skills separately. That way students’ English skills don’t hold them back from progressing on other academic skills on which they can demonstrate mastery.

We are grateful to Joy Nolan, Director of the Mastery Collaborative; Meg Stentz, Associate Director; and Reena Nazir, program consultant, for providing great support for a really informative visit. The other posts in this series will be about the NYC iSchool and the Urban Assembly Maker Academy.

Other posts in this series:

- Diversifying the Student Body and Personalizing Student Schedules at NYC iSchool

- Mastery-Based Making: The Urban Assembly Maker Academy

- What’s College Like for Students from Mastery-Based High Schools?

- Project Example: Mobile App Design at Urban Assembly Maker Academy

See also:

- Catalyzing Mastery-Based Learning: NYC’s Mastery Collaborative

- The Mission and the Message (by Mastery Collaborative staff)

- Mastery Collaborative Overview 2018-19

- Equity Snapshot: The Intersection of Mastery & Culturally Responsive Education

- Moving Toward Mastery: Growing, Developing, and Sustaining Educators for Competency-Based Education

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.